Page Cache, the Affair Between Memory and Files

Previously we looked at how the kernel manages virtual memory for a user process, but files and I/O were left out. This post covers the important and often misunderstood relationship between files and memory and its consequences for performance.

Two serious problems must be solved by the OS when it comes to files. The first one is the mind-blowing slowness of hard drives, and disk seeks in particular, relative to memory. The second is the need to load file contents in physical memory once and share the contents among programs. If you use Process Explorer to poke at Windows processes, you’ll see there are ~15MB worth of common DLLs loaded in every process. My Windows box right now is running 100 processes, so without sharing I’d be using up to ~1.5 GB of physical RAM just for common DLLs. No good. Likewise, nearly all Linux programs need ld.so and libc, plus other common libraries.

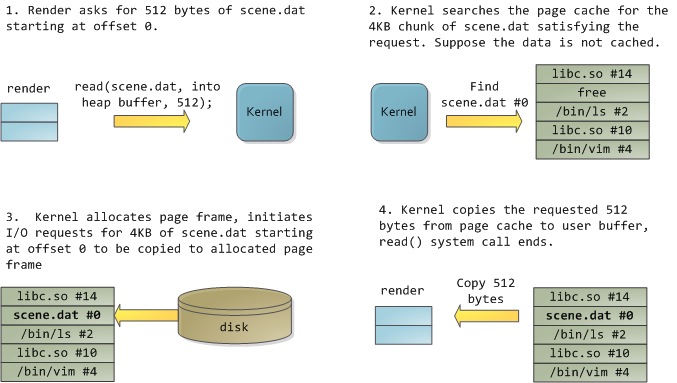

Happily, both problems can be dealt with in one shot: the page cache, where the kernel stores page-sized chunks of files. To illustrate the page cache, I’ll conjure a Linux program named render, which opens file scene.dat and reads it 512 bytes at a time, storing the file contents into a heap-allocated block. The first read goes like this:

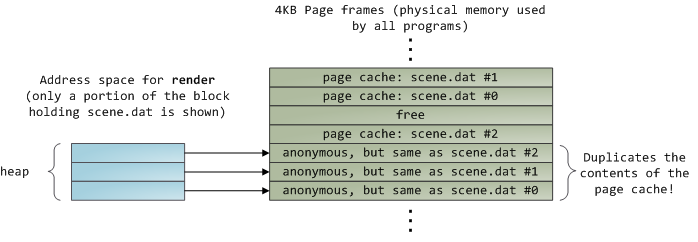

After 12KB have been read, render‘s heap and the relevant page frames look thus:

This looks innocent enough, but there’s a lot going on. First, even though this program uses regular read calls, three 4KB page frames are now in the page cache storing part of scene.dat. People are sometimes surprised by this, but all regular file I/O happens through the page cache. In x86 Linux, the kernel thinks of a file as a sequence of 4KB chunks. If you read a single byte from a file, the whole 4KB chunk containing the byte you asked for is read from disk and placed into the page cache. This makes sense because sustained disk throughput is pretty good and programs normally read more than just a few bytes from a file region. The page cache knows the position of each 4KB chunk within the file, depicted above as #0, #1, etc. Windows uses 256KB views analogous to pages in the Linux page cache.

Sadly, in a regular file read the kernel must copy the contents of the page cache into a user buffer, which not only takes cpu time and hurts the cpu caches, but also wastes physical memory with duplicate data. As per the diagram above, the scene.dat contents are stored twice, and each instance of the program would store the contents an additional time. We’ve mitigated the disk latency problem but failed miserably at everything else. Memory-mapped files are the way out of this madness:

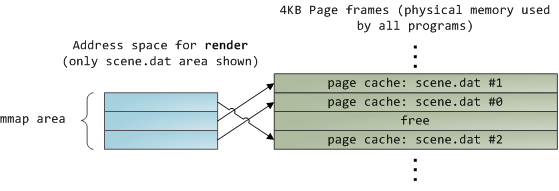

When you use file mapping, the kernel maps your program’s virtual pages directly onto the page cache. This can deliver a significant performance boost: Windows System Programming reports run time improvements of 30% and up relative to regular file reads, while similar figures are reported for Linux and Solaris in Advanced Programming in the Unix Environment. You might also save large amounts of physical memory, depending on the nature of your application.

As always with performance, measurement is everything, but memory mapping earns its keep in a programmer’s toolbox. The API is pretty nice too, it allows you to access a file as bytes in memory and does not require your soul and code readability in exchange for its benefits. Mind your address space and experiment with mmap in Unix-like systems, CreateFileMapping in Windows, or the many wrappers available in high level languages. When you map a file its contents are not brought into memory all at once, but rather on demand via page faults. The fault handler maps your virtual pages onto the page cache after obtaining a page frame with the needed file contents. This involves disk I/O if the contents weren’t cached to begin with.

Now for a pop quiz. Imagine that the last instance of our render program exits. Would the pages storing scene.dat in the page cache be freed immediately? People often think so, but that would be a bad idea. When you think about it, it is very common for us to create a file in one program, exit, then use the file in a second program. The page cache must handle that case. When you think more about it, why should the kernel ever get rid of page cache contents? Remember that disk is 5 orders of magnitude slower than RAM, hence a page cache hit is a huge win. So long as there’s enough free physical memory, the cache should be kept full. It is therefore not dependent on a particular process, but rather it’s a system-wide resource. If you run render a week from now and scene.dat is still cached, bonus! This is why the kernel cache size climbs steadily until it hits a ceiling. It’s not because the OS is garbage and hogs your RAM, it’s actually good behavior because in a way free physical memory is a waste. Better use as much of the stuff for caching as possible.

Due to the page cache architecture, when a program calls write() bytes are simply copied to the page cache and the page is marked dirty. Disk I/O normally does not happen immediately, thus your program doesn’t block waiting for the disk. On the downside, if the computer crashes your writes will never make it, hence critical files like database transaction logs must be fsync()ed (though one must still worry about drive controller caches, oy!). Reads, on the other hand, normally block your program until the data is available. Kernels employ eager loading to mitigate this problem, an example of which is read ahead where the kernel preloads a few pages into the page cache in anticipation of your reads. You can help the kernel tune its eager loading behavior by providing hints on whether you plan to read a file sequentially or randomly (see madvise(), readahead(), Windows cache hints). Linux does read-ahead for memory-mapped files, but I’m not sure about Windows. Finally, it’s possible to bypass the page cache using O_DIRECT in Linux or NO_BUFFERING in Windows, something database software often does.

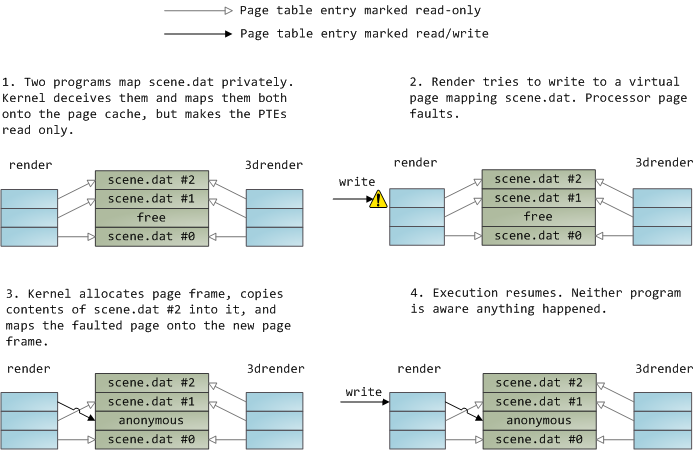

A file mapping may be private or shared. This refers only to updates made to the contents in memory: in a private mapping the updates are not committed to disk or made visible to other processes, whereas in a shared mapping they are. Kernels use the copy on write mechanism, enabled by page table entries, to implement private mappings. In the example below, both render and another program called render3d (am I creative or what?) have mapped scene.dat privately. Render then writes to its virtual memory area that maps the file:

The read-only page table entries shown above do not mean the mapping is read only, they’re merely a kernel trick to share physical memory until the last possible moment. You can see how ‘private’ is a bit of a misnomer until you remember it only applies to updates. A consequence of this design is that a virtual page that maps a file privately sees changes done to the file by other programs as long as the page has only been read from. Once copy-on-write is done, changes by others are no longer seen. This behavior is not guaranteed by the kernel, but it’s what you get in x86 and makes sense from an API perspective. By contrast, a shared mapping is simply mapped onto the page cache and that’s it. Updates are visible to other processes and end up in the disk. Finally, if the mapping above were read-only, page faults would trigger a segmentation fault instead of copy on write.

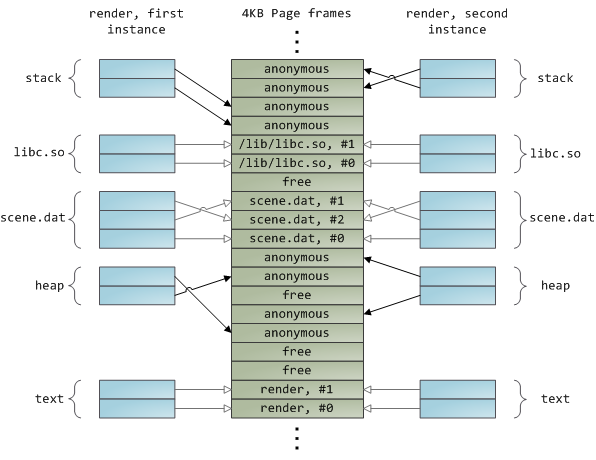

Dynamically loaded libraries are brought into your program’s address space via file mapping. There’s nothing magical about it, it’s the same private file mapping available to you via regular APIs. Below is an example showing part of the address spaces from two running instances of the file-mapping render program, along with physical memory, to tie together many of the concepts we’ve seen.

This concludes our 3-part series on memory fundamentals. I hope the series was useful and provided you with a good mental model of these OS topics. Next week there’s one more post on memory usage figures, and then it’s time for a change of air. Maybe some Web 2.0 gossip or something. ![]()

Page Cache, the Affair Between Memory and Files的更多相关文章

- 工作于内存和文件之间的页缓存, Page Cache, the Affair Between Memory and Files

原文作者:Gustavo Duarte 原文地址:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/post/what-your-computer-does-while-you-wait ...

- Page Cache, the Affair Between Memory and Files.页面缓存-内存与文件的那些事

原文标题:Page Cache, the Affair Between Memory and Files 原文地址:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/ [注:本人水平有限 ...

- Page Cache buffer Cache

https://www.thomas-krenn.com/en/wiki/Linux_Page_Cache_Basics References Jump up ↑ The Buffer Cache ( ...

- (转载)ASP.NET Quiz Answers: Does Page.Cache leak memory?

原文地址:http://blogs.msdn.com/b/tess/archive/2006/08/11/695268.aspx "We use Page.Cache to store te ...

- 【转】Linux Page Cache的工作原理

1 .前言 自从诞生以来,Linux 就被不断完善和普及,目前它已经成为主流通用操作系统之一,使用得非常广泛,它与Windows.UNIX 一起占据了操作系统领域几乎所有的市场份额.特别是在高性能计算 ...

- page cache 与free

我们经常用free查看服务器的内存使用情况,而free中的输出却有些让人困惑,如下: 先看看各个数字的意义以及如何计算得到: free命令输出的第二行(Mem):这行分别显示了物理内存的总量(tota ...

- Linux中的Buffer Cache和Page Cache echo 3 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches Slab内存管理机制 SLUB内存管理机制

Linux中的Buffer Cache和Page Cache echo 3 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches Slab内存管理机制 SLUB内存管理机制 http://w ...

- Linux的page cache使用情况/命中率查看和操控

转载自宋宝华:https://blog.csdn.net/21cnbao/article/details/80458173 这里总结几个Linux文件缓存(page cache)使用情况.命中率查看的 ...

- 从free到page cache

Free 我们经常用free查看服务器的内存使用情况,而free中的输出却有些让人困惑,如下: 图1-1 先看看各个数字的意义以及如何计算得到: free命令输出的第二行(Mem):这行分别显示了 ...

随机推荐

- 【DateStructure】 Charnming usages of Map collection in Java

When learning the usage of map collection in java, I found serveral beneficial methods that was enco ...

- asp.net MVC Razor 语法(3)

编程逻辑:执行基于条件的代码. If 条件 C# 允许您执行基于条件的代码. 如需测试某个条件,您可以使用 if 语句.if 语句会基于您的测试来返回 true 或 false: if 语句启动代码块 ...

- web - 清除浮动

最理想的方式为 伪类 + content : 例如 div:after{content:"";display:block;clear:both;} div{zoom:1;} 另外, ...

- <转>ASP.NET学习笔记之理解MVC底层运行机制

ASP.NET MVC架构与实战系列之一:理解MVC底层运行机制 今天,我将开启一个崭新的话题:ASP.NET MVC框架的探讨.首先,我们回顾一下ASP.NET Web Form技术与ASP.NET ...

- PL/SQL编程要点和注意点

http://www.itpub.net/thread-1560427-3-1.html 1. 非关键字小写,关键字大写,用下划线分隔,用前缀区分变量与表列名.不强求变量初始值.2. 永远只捕获可预测 ...

- C++ try catch 捕获空指针异常,数组越界异常

#include <exception> #include <iostream> using namespace std; /************************* ...

- Android ActionBar详解(三)--->ActionBar的Home导航功能

FirstActivity如下: package cc.testsimpleactionbar2; import android.os.Bundle; import android.app.Activ ...

- javascript小练习—记住密码提示框

px/px solid redpxpx]; var oTips = document.getElementById("tips"); oP.onmousemove = functi ...

- DDR、DDR2、DDR3产品区别

DDR采用一个周期来回传递一次数据,因此传输在同时间加倍,因此就像工作在两倍的工作频率一样.为了直观,以等效的方式命名,因此命名为DDR 200 266 333 400. DDR2尽管工作频率没有变化 ...

- 关于 overridePendingTransition()使用

实现两个 Activity 切换时的动画.在Activity中使用有两个参数:进入动画和出去的动画. 注意1.必须在 StartActivity() 或 finish() 之后立即调用.2.而且在 ...