Memory Layout for Multiple and Virtual Inheritance

Memory Layout for Multiple and Virtual Inheritance

(By Edsko de Vries, January 2006)

Warning. This article is rather technical and assumes a good knowledge of C++ and some assembly language.

In this article we explain the object layout implemented by gcc for multiple and virtual inheritance.

Although in an ideal world C++ programmers should not need to know these details of the compiler internals,

unfortunately the way multiple (and especially virtual) inheritance is implemented has various non-obvious

consequences for writing C++ code (in particular, for downcasting pointers, using pointers to pointers, and

the invocation order of constructors for virtual bases). If you understand how multiple inheritance is

implemented, you will be able anticipate these consequences and deal with them in your code. Also, it is

useful to understand the cost of using virtual inheritance if you care about efficiency. Finally, it is

interesting :-)

Multiple Inheritance

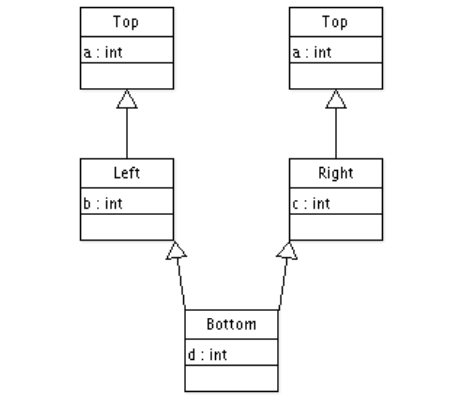

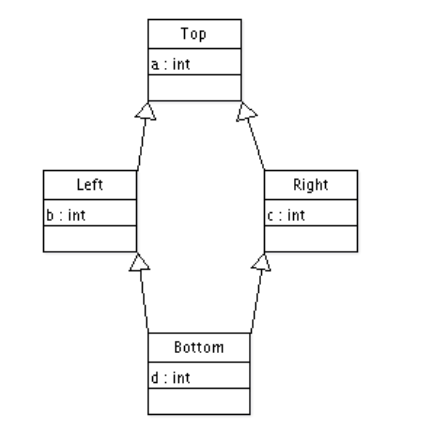

First we consider the relatively simple case of (non-virtual) multiple inheritance. Consider the following

C++ class hierarchy.

class Top

{p

ublic:

int a;

};

class Left : public Top

{p

ublic:

int b;

};

class Right : public Top

{p

ublic:

int c;

};

class Bottom : public Left, public Right

{p

ublic:

int d;

};

Using a UML diagram, we can represent this hierarchy as

Note that Top is inherited from twice (this is known as repeated inheritance in Eiffel). This means that an

object bottom of type Bottom will have two attributes called a (accessed as bottom.Left::a and

bottom.Right::a).

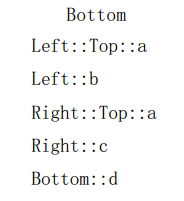

How are Left, Right and Bottom laid out in memory? We show the simplest case first. Left and Right have the

following structure:

Note that the first attribute is the attribute inherited from Top. This means that after the following two

assignments

Left* left = new Left();

Top* top = left;

left and top can point to the exact same address, and we can treat the Left object as if it were a Top object

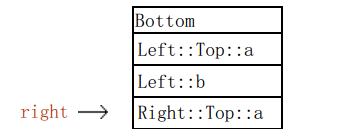

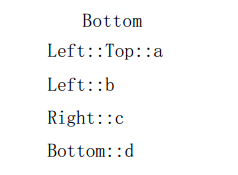

(and obviously a similar thing happens for Right). What about Bottom? gcc suggests

Now what happens when we upcast a Bottom pointer?

Bottom* bottom = new Bottom();

Left* left = bottom;

This works out nicely. Because of the memory layout, we can treat an object of type Bottom as if it were an

object of type Left, because the memory layout of both classes coincide. However, what happens when we upcast

to Right?

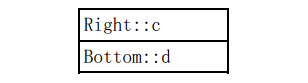

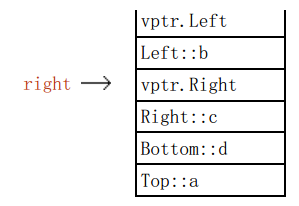

Right* right = bottom;

For this to work, we have to adjust the pointer value to make it point to the corresponding section of the

Bottom layout:

After this adjustment, we can access bottom through the right pointer as a normal Right object; however,

bottom and right now point to different memory locations. For completeness' sake, consider what would happen

when we do

Top* top = bottom;

Right, nothing at all. This statement is ambiguous: the compiler will complain

error: `Top' is an ambiguous base of `Bottom'

The two possibilities can be disambiguated using

Top* topL = (Left*) bottom;

Top* topR = (Right*) bottom;

After these two assignments, topL and left will point to the same address, as will topR and right.

Virtual Inheritance

To avoid the repeated inheritance of Top, we must inherit virtually from Top:

class Top

{p

ublic:

int a;

};

class Left : virtual public Top

{p

ublic:

int b;

};

class Right : virtual public Top

{p

ublic:

int c;

};

class Bottom : public Left, public Right

{p

ublic:

int d;

};

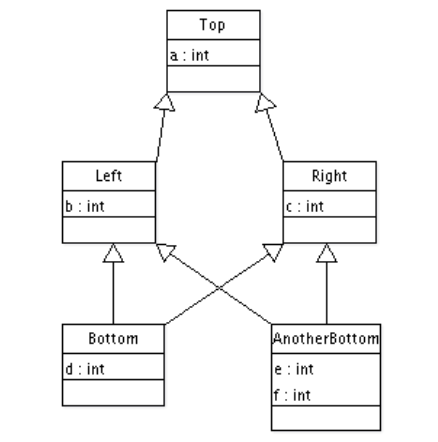

This yields the following hierarchy (which is perhaps what you expected in the first place)

while this may seem more obvious and simpler from a programmer's point of view, from the compiler's point of

view, this is vastly more complicated. Consider the layout of Bottom again. One (non) possibility is

The advantage of this layout is that the first part of the layout collides with the layout of Left, and we

can thus access a Bottom easily through a Left pointer. However, what are we going to do with

Right* right = bottom;

Which address do we assign to right? After this assignment, we should be able to use right as if it were

pointing to a regular Right object. However, this is impossible! The memory layout of Right itself is

completely different, and we can thus no longer access a “real” Right object in the same way as an upcasted

Bottom object. Moreover, no other (simple) layout for Bottom will work.

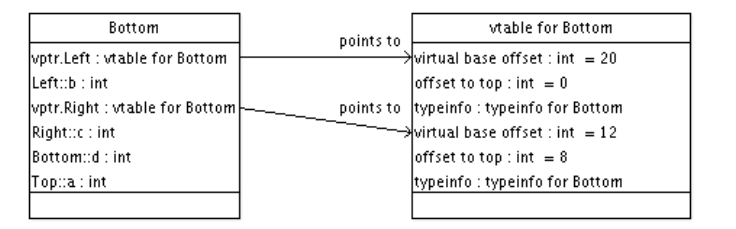

The solution is non-trivial. We will show the solution first and then explain it.

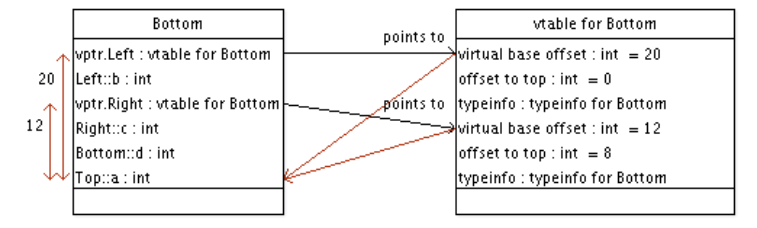

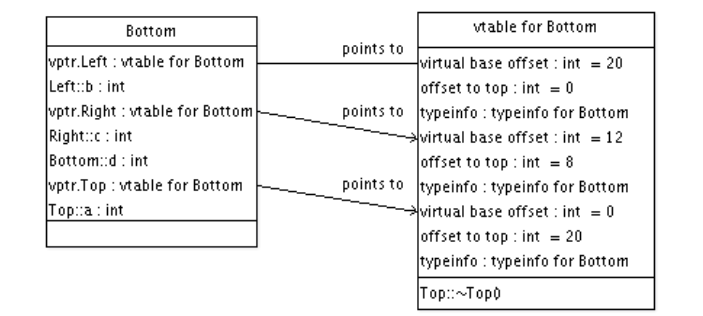

You should note two things in this diagram. First, the order of the fields is completely different (in fact,

it is approximately the reverse). Second, there are these new vptr pointers. These attributes are

automatically inserted by the compiler when necessary (when using virtual inheritance, or when using virtual

functions). The compiler also inserts code into the constructor to initialise these pointers.

The vptrs (virtual pointers) index a “virtual table”. There is a vptr for every virtual base of the class.

To see how the virtual table (vtable) is used, consider the following C++ code

Bottom* bottom = new Bottom();

Left* left = bottom;

int p = left->a;

The second assignment makes left point to the same address as bottom (i.e., it points to the “top” of the

Bottom object). We consider the compilation of the last assignment (slightly simplified):

movl left, %eax # %eax = left

movl (%eax), %eax # %eax = left.vptr.Left

movl (%eax), %eax # %eax = virtual base offset

addl left, %eax # %eax = left + virtual base offset

movl (%eax), %eax # %eax = left.a

movl %eax, p # p = left.a

In words, we use left to index the virtual table and obtain the “virtual base offset” (vbase). This offset

is then added to left, which is then used to index the Top section of the Bottom object. From the diagram,

you can see that the virtual base offset for Left is 20; if you assume that all the fields in Bottom are 4

bytes, you will see that adding 20 bytes to left will indeed point to the a field.

With this setup, we can access the Right part the same way. After

Bottom* bottom = new Bottom();

Right* right = bottom;

int p = right->a;

right will point to the appropriate part of the Bottom object:

The assignment to p can now be compiled in the exact same way as we did previously for Left. The only

difference is that the vptr we access now points to a different part of the virtual table: the virtual base

offset we obtain is 12, which is correct (verify!). We can summarise this visually:

Of course, the point of the exercise was to be able to access real Right objects the same way as upcasted

Bottom objects. So, we have to introduce vptrs in the layout of Right (and Left) too:

Now we can access a Bottom object through a Right pointer without further difficulty. However, this has come

at rather large expense: we needed to introduce virtual tables, classes needed to be extended with one or

more virtual pointers, and a simple attribute lookup in an object now needs two indirections through the

virtual table (although compiler optimizations can reduce that cost somewhat).

Downcasting

As we have seen, casting a pointer of type DerivedClass to a pointer of type SuperClass (in other words,

upcasting) may involve adding an offset to the pointer. One might be tempted to think that downcasting (going

the other way) can then simply be implemented by subtracting the same offset. And indeed, this is the case

for non-virtual inheritance. However, virtual inheritance (unsurprisingly!) introduces another complication.

Suppose we extend our inheritance hierarchy with the following class.

class AnotherBottom : public Left, public Right

{p

ublic:

int e;

int f;

};

The hierarchy now looks like

Now consider the following code.

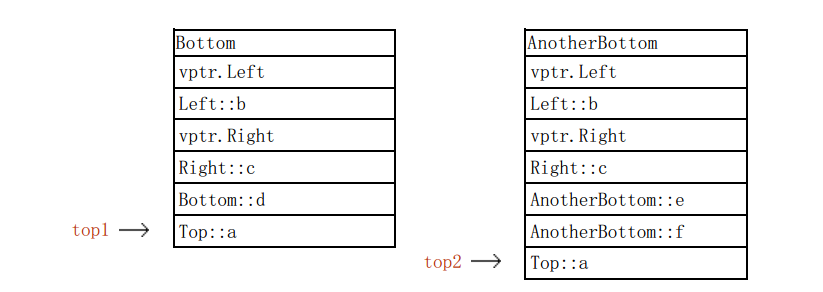

Bottom* bottom1 = new Bottom();

AnotherBottom* bottom2 = new AnotherBottom();

Top* top1 = bottom1;

Top* top2 = bottom2;

Left* left = static_cast<Left*>(top1);

The following diagram shows the layout of Bottom and AnotherBottom, and shows where top is pointing after the

last assignment.

Now consider how to implement the static cast from top1 to left, while taking into account that we do not

know whether top1 is pointing to an object of type Bottom or an object of type AnotherBottom. It can't be

done! The necessary offset depends on the runtime type of top1 (20 for Bottom and 24 for AnotherBottom). The

compiler will complain:

error: cannot convert from base `Top' to derived type `Left'

via virtual base `Top'

Since we need runtime information, we need to use a dynamic cast instead:

Left* left = dynamic_cast<Left*>(top1);

However, the compiler is still unhappy:

error: cannot dynamic_cast `top' (of type `class Top*') to type

`class Left*' (source type is not polymorphic)

The problem is that a dynamic cast (as well as use of typeid) needs runtime type information about the object

pointed to by top1. However, if you look at the diagram, you will see that all we have at the location

pointed to by top1 is an integer (a). The compiler did not include a vptr.Top because it did not think that

was necessary. To force the compiler to include this vptr, we can add a virtual destructor to Top:

class Top

{

public:

virtual ~Top() {}

int a;

};

This change necessitates a vptr for Top. The new layout for Bottom is

(Of course, the other classes get a similar new vptr.Top attribute). The compiler now inserts a library call

for the dynamic cast:

left = __dynamic_cast(top1, typeinfo_for_Top, typeinfo_for_Left, -);

This function __dynamic_cast is defined in libstdc++ (the corresponding header file is cxxabi.h); armed with

the type information for Top, Left and Bottom (through vptr.Top), the cast can be executed. (The -1 parameter

indicates that the relationship between Left and Top is presently unknown). For details, refer to the

implementation in tinfo.cc.

Concluding Remarks

Finally, we tie a couple of loose ends.

(In)variance of Double Pointers

This is were it gets slightly confusing, although it is rather obvious when you give it some thought. We

consider an example. Assume the class hierarchy presented in the last section (Downcasting). We have seen

previously what the effect is of

Bottom* b = new Bottom();

Right* r = b;

(the value of b gets adjusted by 8 bytes before it is assigned to r, so that it points to the Right section

of the Bottom object). Thus, we can legally assign a Bottom* to a Right*. What about Bottom** and Right**?

Bottom** bb = &b;

Right** rr = bb;

Should the compiler accept this? A quick test will show that the compiler will complain:

error: invalid conversion from `Bottom**' to `Right**'

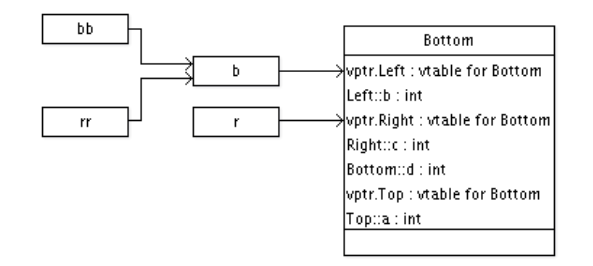

Why? Suppose the compiler would accept the assignment of bb to rr. We can visualise the result as:

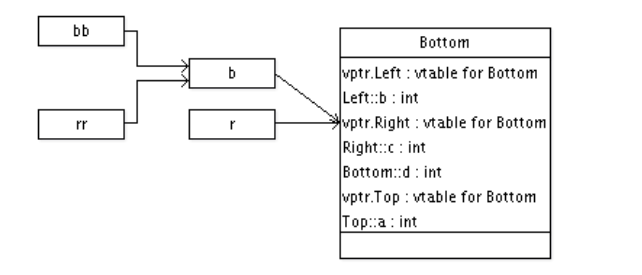

So, bb and rr both point to b, and b and r point to the appropriate sections of the Bottom object. Now consider what happens when we assign to *rr (note that the type of *rr is Right*, so this assignment is

valid):

*rr = b;

This is essentially the same assignment as the assignment to r above. Thus, the compiler will implement it

the same way! In particular, it will adjust the value of b by 8 bytes before it assigns it to *rr. But *rr

pointed to b! If we visualise the result again:

This is correct as long as we access the Bottom object through *rr, but as soon as we access it through b

itself, all memory references will be off by 8 bytes — obviously a very undesirable situation.

So, in summary, even if *a and *b are related by some subtyping relation, **a and **b are not.

Constructors of Virtual Bases

The compiler must guarantee that all virtual pointers of an object are properly initialised. In particular,

it guarantees that the constructor for all virtual bases of a class get invoked, and get invoked only once.

If you don't explicitly call the constructors of your virtual superclasses (independent of how far up the

tree they are), the compiler will automatically insert a call to their default constructors.

This can lead to some unexpected results. Consider the same class hierarchy again we have been considering so

far, extended with constructors:

class Top

{p

ublic:

Top() { a = -; }

Top(int _a) { a = _a; }

int a;

};

class Left : public Top

{p

ublic:

Left() { b = -; }

Left(int _a, int _b) : Top(_a) { b = _b; }

int b;

};

class Right : public Top

{p

ublic:

Right() { c = -; }

Right(int _a, int _c) : Top(_a) { c = _c; }

int c;

};

class Bottom : public Left, public Right

{p

ublic:

Bottom() { d = -; }

Bottom(int _a, int _b, int _c, int _d) : Left(_a, _b), Right(_a, _c)

{

d = _d;

}

int d;

};

(We consider the non-virtual case first.) What would you expect this to output:

Bottom bottom(,,,);

printf("%d %d %d %d %d\n", bottom.Left::a, bottom.Right::a,

bottom.b, bottom.c, bottom.d);

You would probably expect (and get)

However, now consider the virtual case (where we inherit virtually from Top). If we make that single change,

and run the program again, we instead get

- -

Why? If you trace the execution of the constructors, you will find

Top::Top()

Left::Left(,)

Right::Right(,)

Bottom::Bottom(,,,)

As explained above, the compiler has inserted a call to the default constructor in Bottom, before the

execution of the other constructors. Then when Left tries to call its superconstructor (Top), we find that

Top has already been initialised and the constructor does not get invoked.

To avoid this situation, you should explicitly call the constructor of your virtual base(s):

Bottom(int _a, int _b, int _c, int _d): Top(_a), Left(_a,_b), Right(_a,_c)

{

d = _d;

}

Pointer Equivalence

Once again assuming the same (virtual) class hierarchy, would you expect this to print “Equal”?

Bottom* b = new Bottom();

Right* r = b;

if(r == b)

printf("Equal!\n");

Bear in mind that the two addresses are not actually equal (r is off by 8 bytes). However, that should be

completely transparent to the user; so, the compiler actually subtracts the 8 bytes from r before comparing

it to b; thus, the two addresses are considered equal.

Casting to void*

Finally, we consider what happens we can cast an object to void*. The compiler must guarantee that a pointer

cast to void* points to the “top” of the object. Using the vtable, this is actually very easy to implement.

You may have been wondering what the offset to top field is. It is the offset from the vptr to the top of the

object. So, a cast to void* can be implemented using a single lookup in the vtable. Make sure to use a

dynamic cast, however, thus:

dynamic_cast<void*>(b);

Memory Layout for Multiple and Virtual Inheritance的更多相关文章

- Memory Layout (Virtual address space of a C process)

Memory Layout (Virtual address space of a C process) 分类: C语言基础2012-12-06 23:16 2174人阅读 评论(0) 收藏 举报 f ...

- Kernel Memory Layout on ARM Linux

这是内核自带的文档,讲解ARM芯片的内存是如何布局的!比较简单,对于初学者可以看一下!但要想深入理解Linux内存管理,建议还是找几本好书看看,如深入理解Linux虚拟内存,嵌入系统分析,Linux内 ...

- Memory Layout of C Programs

Memory Layout of C Programs A typical memory representation of C program consists of following sec ...

- 【ARM-Linux开发】Linux内存管理:ARM Memory Layout以及mmu配置

原文:Linux内存管理:ARM Memory Layout以及mmu配置 在内核进行page初始化以及mmu配置之前,首先需要知道整个memory map. 1. ARM Memory Layout ...

- C++: virtual inheritance and Cross Delegation

Link1: Give an example Note: I think the Storable::Write method should also be pure virtual. http:// ...

- Use Memory Layout from Target Dialog Scatter File

参考 MDK-ARM Linker Scatter File的用法(转载) keil报错 Rebuild target 'Target 1' assembling test1.s... linking ...

- PatentTips - Method to manage memory in a platform with virtual machines

BACKGROUND INFORMATION Various mechanisms exist for managing memory in a virtual machine environment ...

- System and method for parallel execution of memory transactions using multiple memory models, including SSO, TSO, PSO and RMO

A data processor supports the use of multiple memory models by computer programs. At a device extern ...

- [译]rabbitmq 2.4 Multiple tenants: virtual hosts and separation

我对rabbitmq学习还不深入,这些翻译仅仅做资料保存,希望不要误导大家. With exchanges, bindings, and queues under your belt, you mig ...

随机推荐

- Mac 系统占用100g的解决办法

Mac 关于本机-磁盘管理,如果发现系统占用超过80g以上的小伙伴们可以做以下操作只需要以下4个步骤,轻松降到30g以内!!!!!!!(仅适用于安装了Xcode的小伙伴) 打开Finder,comma ...

- [Web][DreamweaverCS6][高中同学毕业分布去向网站+服务器上挂载]一、安装与破解DreamweaverCS6+基本规划

DreamweaverCS6安装与破解 一.背景介绍:同学毕业分布图项目计划简介 哎哎哎,炸么说呢,对于Web前端设计来说,纯手撕html部分代码实在是难受. 对于想做地图这类的就“必须”用这个老工具 ...

- reStructuredText文件语法简单学习

reStructuredText 是一种扩展名为.rst的纯文本文件,通过特定的解释器,能够将文本中的内容输出为特定的格式 1. 章节标题 章节头部由下线(也可有上线)和包含标点的标题组合创建,其中下 ...

- 关于 MongoDB 与 SQL Server 通过本身自带工具实现数据快速迁移 及 注意事项 的探究

背景介绍 随着业务的发展.需求的变化,促使我们追求使用不同类型的数据库,充分发挥其各自特性.如果决定采用新类型的数据库,就需要将既有的数据迁移到新的数据库中.在这类需求中,将SQL Server中的数 ...

- Python装饰器、内置函数之金兰契友

装饰器:装饰器的实质就是一个闭包,而闭包又是嵌套函数的一种.所以也可以理解装饰器是一种特殊的函数.因为程序一般都遵守开放封闭原则,软件在设计初期不可能把所有情况都想到,所以一般软件都支持功能上的扩展, ...

- AXI-Lite总线及其自定义IP核使用分析总结

ZYNQ的优势在于通过高效的接口总线组成了ARM+FPGA的架构.我认为两者是互为底层的,当进行算法验证时,ARM端现有的硬件控制器和库函数可以很方便地连接外设,而不像FPGA设计那样完全写出接口时序 ...

- SQLServer之创建INSTEAD OF INSERT,UPDATE,DELETE触发器

INSTEAD OF触发器工作原理 INSTEAD OF表示并不执行其所定义的操作INSERT,UPDATE ,DELETE,而仅是执行触发器本身,即当对表进行INSERT.UPDATE 或 DELE ...

- Python面试常见的问题

So if you are looking forward to a Python Interview, here are some most probable questions to be ask ...

- TableExistsException: hbase:namespace

解决:zookeeper还保留着上一次的Hbase设置,所以造成了冲突.删除zookeeper信息,重启之后就没问题了 1.切换到zookeeper的bin目录: 2.执行$sh zkCli.sh 输 ...

- VS 附加到进程 加载“附加进程”弹窗很慢

最近遇到一个问题,点击Ctrl + Alt + P 附加到进程的时候,弹出下图弹窗“附加到进程”很慢. 找了很多原因,后来发现,是因为少安装了一个插件,安装后,弹窗的耗时明显少了. 下载 Win ...