BAYESIAN STATISTICS AND CLINICAL TRIAL CONCLUSIONS: WHY THE OPTIMSE STUDY SHOULD BE CONSIDERED POSITIVE(转)

Statistical approaches to randomised controlled trial analysis

The statistical approach used in the design and analysis of the vast majority of clinical studies is often referred to as classical or frequentist. Conclusions are made on the results of hypothesis tests with generation of p-values and confidence intervals, and require that the correct conclusion be drawn with a high probability among a notional set of repetitions of the trial.

Bayesian inference is an alternative, which treats conclusions probabilistically and provides a different framework for thinking about trial design and conclusions. There are many differences between the two, but for this discussion there are two obvious distinctions with the Bayesian approach. The first is that prior knowledge can be accounted for to a greater or lesser extent, something life scientists sometimes have difficulty reconciling. Secondly, the conclusions of a Bayesian analysis often focus on the decision that requires to be made, e.g. should this new treatment be used or not.

There are pros and cons to both sides, nicely discussed here, but I would argue that the results of frequentist analyses are too often accepted with insufficient criticism. Here’s a good example.

OPTIMSE: Optimisation of Cardiovascular Management to Improve Surgical Outcome

Optimising the amount of blood being pumped out of the heart during surgery may improve patient outcomes. By specifically measuring cardiac output in the operating theatre and using it to guide intravenous fluid administration and the use of drugs acting on the circulation, the amount of oxygen that is delivered to tissues can be increased.

It sounds like common sense that this would be a good thing, but drugs can have negative effects, as can giving too much intravenous fluid. There are also costs involved, is the effort worth it? Small trials have suggested that cardiac output-guided therapy may have benefits, but the conclusion of a large Cochrane review was that the results remain uncertain.

A well designed and run multi-centre randomised controlled trial was performed to try and determine if this intervention was of benefit (OPTIMSE: Optimisation of Cardiovascular Management to Improve Surgical Outcome).

Patients were randomised to a cardiac output–guided hemodynamic therapy algorithm for intravenous fluid and a drug to increase heart muscle contraction (the inotrope, dopexamine) during and 6 hours following surgery (intervention group) or to usual care (control group).

The primary outcome measure was the relative risk (RR) of a composite of 30-day moderate or major complications and mortality.

OPTIMSE: reported results

Focusing on the primary outcome measure, there were 158/364 (43.3%) and 134/366 (36.6%) patients with complication/mortality in the control and intervention group respectively. Numerically at least, the results appear better in the intervention group compared with controls.

Using the standard statistical approach, the relative risk (95% confidence interval) = 0.84 (0.70-1.01), p=0.07 and absolute risk difference = 6.8% (−0.3% to 13.9%), p=0.07. This is interpreted as there being insufficient evidence that the relative risk for complication/death is different to 1.0 (all analyses replicated below). The authors reasonably concluded that:

In a randomized trial of high-risk patients undergoing major gastrointestinal surgery, use of a cardiac output–guided hemodynamic therapy algorithm compared with usual care did not reduce a composite outcome of complications and 30-day mortality.

A difference does exist between the groups, but is not judged to be a sufficient difference using this conventional approach.

OPTIMSE: Bayesian analysis

Repeating the same analysis using Bayesian inference provides an alternative way to think about this result. What are the chances the two groups actually do have different results? What are the chances that the two groups have clinically meaningful differences in results? What proportion of patients stand to benefit from the new intervention compared with usual care?

With regard to prior knowledge, this analysis will not presume any prior information. This makes the point that prior information is not always necessary to draw a robust conclusion. It may be very reasonable to use results from pre-existing meta-analyses to specify a weak prior, but this has not been done here. Very grateful to John Kruschke for the excellent scripts and book, Doing Bayesian Data Analysis.

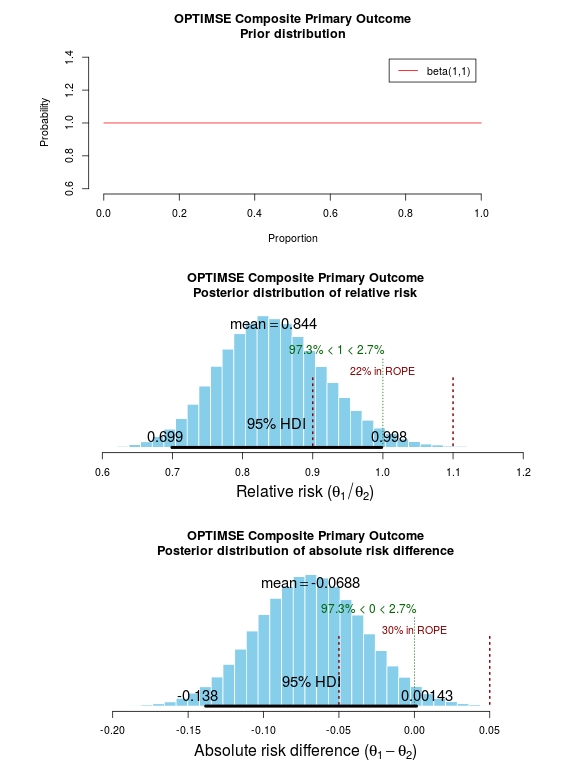

The results of the analysis are presented in the graph below. The top panel is the prior distribution. All proportions for the composite outcome in both the control and intervention group are treated as equally likely.

The middle panel contains the main findings. This is the posterior distribution generated in the analysis for the relative risk of the composite primary outcome (technical details in script below).

The mean relative risk = 0.84 which as expected is the same as the frequentist analysis above. Rather than confidence intervals, in Bayesian statistics a credible interval or region is quoted (HDI = highest density interval is the same). This is philosphically different to a confidence interval and says:

Given the observed data, there is a 95% probability that the true RR falls within this credible interval.

This is a subtle distinction to the frequentist interpretation of a confidence interval:

Were I to repeat this trial multiple times and compute confidence intervals, there is a 95% probability that the true RR would fall within these confidence intervals.

This is an important distinction and can be extended to make useful probabilistic statements about the result.

The figures in green give us the proportion of the distribution above and below 1.0. We can therefore say:

The probability that the intervention group has a lower incidence of the composite endpoint is 97.3%.

It may be useful to be more specific about the size of difference between the control and treatment group that would be considered equivalent, e.g. 10% above and below a relative risk = 1.0. This is sometimes called the region of practical equivalence (ROPE; red text on plots). Experts would determine what was considered equivalent based on many factors. We could therefore say:

The probability of the composite end-point for the control and intervention group being equivalent is 22%.

Or, the probability of a clinically relevant difference existing in the composite endpoint between control and intervention groups is 78%

Finally, we can use the 200 000 estimates of the probability of complication/death in the control and intervention groups that were generated in the analysis (posterior prediction). In essence, we can act like these are 2 x 200 000 patients. For each “patient pair”, we can use their probability estimates and perform a random draw to simulate the occurrence of complication/death. It may be useful then to look at the proportion of “patients pairs” where the intervention patient didn’t have a complication but the control patient did:

Finally, we can use the 200 000 estimates of the probability of complication/death in the control and intervention groups that were generated in the analysis (posterior prediction). In essence, we can act like these are 2 x 200 000 patients. For each “patient pair”, we can use their probability estimates and perform a random draw to simulate the occurrence of complication/death. It may be useful then to look at the proportion of “patients pairs” where the intervention patient didn’t have a complication but the control patient did:

Using posterior prediction on the generated Bayesian model, the probability that a patient in the intervention group did not have a complication/death when a patient in the control group did have a complication/death is 28%.

Conclusion

On the basis of a standard statistical analysis, the OPTIMISE trial authors reasonably concluded that the use of the intervention compared with usual care did not reduce a composite outcome of complications and 30-day mortality.

Using a Bayesian approach, it could be concluded with 97.3% certainty that use of the intervention compared with usual care reduces the composite outcome of complications and 30-day mortality; that with 78% certainty, this reduction is clinically significant; and that in 28% of patients where the intervention is used rather than usual care, complication or death may be avoided.

# OPTIMISE trial in a Bayesian framework

# JAMA. 2014;311(21):2181-2190. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.5305

# Ewen Harrison

# 15/02/2015 # Primary outcome: composite of 30-day moderate or major complications and mortality

N1 <- 366

y1 <- 134

N2 <- 364

y2 <- 158

# N1 is total number in the Cardiac Output–Guided Hemodynamic Therapy Algorithm (intervention) group

# y1 is number with the outcome in the Cardiac Output–Guided Hemodynamic Therapy Algorithm (intervention) group

# N2 is total number in usual care (control) group

# y2 is number with the outcome in usual care (control) group # Risk ratio

(y1/N1)/(y2/N2) library(epitools)

riskratio(c(N1-y1, y1, N2-y2, y2), rev="rows", method="boot", replicates=100000) # Using standard frequentist approach

# Risk ratio (bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals) = 0.84 (0.70-1.01)

# p=0.07 (Fisher exact p-value) # Reasonably reported as no difference between groups. # But there is a difference, it just not judged significant using conventional

# (and much criticised) wisdom. # Bayesian analysis of same ratio

# Base script from John Krushcke, Doing Bayesian Analysis #------------------------------------------------------------------------------

source("~/Doing_Bayesian_Analysis/openGraphSaveGraph.R")

source("~/Doing_Bayesian_Analysis/plotPost.R")

require(rjags) # Kruschke, J. K. (2011). Doing Bayesian Data Analysis, Academic Press / Elsevier.

#------------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Important

# The model will be specified with completely uninformative prior distributions (beta(1,1,).

# This presupposes that no pre-exisiting knowledge exists as to whehther a difference

# may of may not exist between these two intervention. # Plot Beta(1,1)

# 3x1 plots

par(mfrow=c(3,1))

# Adjust size of prior plot

par(mar=c(5.1,7,4.1,7))

plot(seq(0, 1, length.out=100), dbeta(seq(0, 1, length.out=100), 1, 1),

type="l", xlab="Proportion",

ylab="Probability",

main="OPTIMSE Composite Primary Outcome\nPrior distribution",

frame=FALSE, col="red", oma=c(6,6,6,6))

legend("topright", legend="beta(1,1)", lty=1, col="red", inset=0.05) # THE MODEL.

modelString = "

# JAGS model specification begins here...

model {

# Likelihood. Each complication/death is Bernoulli.

for ( i in 1 : N1 ) { y1[i] ~ dbern( theta1 ) }

for ( i in 1 : N2 ) { y2[i] ~ dbern( theta2 ) }

# Prior. Independent beta distributions.

theta1 ~ dbeta( 1 , 1 )

theta2 ~ dbeta( 1 , 1 )

}

# ... end JAGS model specification

" # close quote for modelstring # Write the modelString to a file, using R commands:

writeLines(modelString,con="model.txt") #------------------------------------------------------------------------------

# THE DATA. # Specify the data in a form that is compatible with JAGS model, as a list:

dataList = list(

N1 = N1 ,

y1 = c(rep(1, y1), rep(0, N1-y1)),

N2 = N2 ,

y2 = c(rep(1, y2), rep(0, N2-y2))

) #------------------------------------------------------------------------------

# INTIALIZE THE CHAIN. # Can be done automatically in jags.model() by commenting out inits argument.

# Otherwise could be established as:

# initsList = list( theta1 = sum(dataList$y1)/length(dataList$y1) ,

# theta2 = sum(dataList$y2)/length(dataList$y2) ) #------------------------------------------------------------------------------

# RUN THE CHAINS. parameters = c( "theta1" , "theta2" ) # The parameter(s) to be monitored.

adaptSteps = 500 # Number of steps to "tune" the samplers.

burnInSteps = 1000 # Number of steps to "burn-in" the samplers.

nChains = 3 # Number of chains to run.

numSavedSteps=200000 # Total number of steps in chains to save.

thinSteps=1 # Number of steps to "thin" (1=keep every step).

nIter = ceiling( ( numSavedSteps * thinSteps ) / nChains ) # Steps per chain.

# Create, initialize, and adapt the model:

jagsModel = jags.model( "model.txt" , data=dataList , # inits=initsList ,

n.chains=nChains , n.adapt=adaptSteps )

# Burn-in:

cat( "Burning in the MCMC chain...\n" )

update( jagsModel , n.iter=burnInSteps )

# The saved MCMC chain:

cat( "Sampling final MCMC chain...\n" )

codaSamples = coda.samples( jagsModel , variable.names=parameters ,

n.iter=nIter , thin=thinSteps )

# resulting codaSamples object has these indices:

# codaSamples[[ chainIdx ]][ stepIdx , paramIdx ] #------------------------------------------------------------------------------

# EXAMINE THE RESULTS. # Convert coda-object codaSamples to matrix object for easier handling.

# But note that this concatenates the different chains into one long chain.

# Result is mcmcChain[ stepIdx , paramIdx ]

mcmcChain = as.matrix( codaSamples ) theta1Sample = mcmcChain[,"theta1"] # Put sampled values in a vector.

theta2Sample = mcmcChain[,"theta2"] # Put sampled values in a vector. # Plot the chains (trajectory of the last 500 sampled values).

par( pty="s" )

chainlength=NROW(mcmcChain)

plot( theta1Sample[(chainlength-500):chainlength] ,

theta2Sample[(chainlength-500):chainlength] , type = "o" ,

xlim = c(0,1) , xlab = bquote(theta[1]) , ylim = c(0,1) ,

ylab = bquote(theta[2]) , main="JAGS Result" , col="skyblue" ) # Display means in plot.

theta1mean = mean(theta1Sample)

theta2mean = mean(theta2Sample)

if (theta1mean > .5) { xpos = 0.0 ; xadj = 0.0

} else { xpos = 1.0 ; xadj = 1.0 }

if (theta2mean > .5) { ypos = 0.0 ; yadj = 0.0

} else { ypos = 1.0 ; yadj = 1.0 }

text( xpos , ypos ,

bquote(

"M=" * .(signif(theta1mean,3)) * "," * .(signif(theta2mean,3))

) ,adj=c(xadj,yadj) ,cex=1.5 ) # Plot a histogram of the posterior differences of theta values.

thetaRR = theta1Sample / theta2Sample # Relative risk

thetaDiff = theta1Sample - theta2Sample # Absolute risk difference par(mar=c(5.1, 4.1, 4.1, 2.1))

plotPost( thetaRR , xlab= expression(paste("Relative risk (", theta[1]/theta[2], ")")) ,

compVal=1.0, ROPE=c(0.9, 1.1),

main="OPTIMSE Composite Primary Outcome\nPosterior distribution of relative risk")

plotPost( thetaDiff , xlab=expression(paste("Absolute risk difference (", theta[1]-theta[2], ")")) ,

compVal=0.0, ROPE=c(-0.05, 0.05),

main="OPTIMSE Composite Primary Outcome\nPosterior distribution of absolute risk difference") #-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Use posterior prediction to determine proportion of cases in which

# using the intervention would result in no complication/death

# while not using the intervention would result in complication death chainLength = length( theta1Sample ) # Create matrix to hold results of simulated patients:

yPred = matrix( NA , nrow=2 , ncol=chainLength ) # For each step in chain, use posterior prediction to determine outcome

for ( stepIdx in 1:chainLength ) { # step through the chain

# Probability for complication/death for each "patient" in intervention group:

pDeath1 = theta1Sample[stepIdx]

# Simulated outcome for each intervention "patient"

yPred[1,stepIdx] = sample( x=c(0,1), prob=c(1-pDeath1,pDeath1), size=1 )

# Probability for complication/death for each "patient" in control group:

pDeath2 = theta2Sample[stepIdx]

# Simulated outcome for each control "patient"

yPred[2,stepIdx] = sample( x=c(0,1), prob=c(1-pDeath2,pDeath2), size=1 )

} # Now determine the proportion of times that the intervention group has no complication/death

# (y1 == 0) and the control group does have a complication or death (y2 == 1))

(pY1eq0andY2eq1 = sum( yPred[1,]==0 & yPred[2,]==1 ) / chainLength)

(pY1eq1andY2eq0 = sum( yPred[1,]==1 & yPred[2,]==0 ) / chainLength)

(pY1eq0andY2eq0 = sum( yPred[1,]==0 & yPred[2,]==0 ) / chainLength)

(pY10eq1andY2eq1 = sum( yPred[1,]==1 & yPred[2,]==1 ) / chainLength) # Conclusion: in 27% of cases based on these probabilities,

# a patient in the intervention group would not have a complication,

# when a patient in control group did.

BAYESIAN STATISTICS AND CLINICAL TRIAL CONCLUSIONS: WHY THE OPTIMSE STUDY SHOULD BE CONSIDERED POSITIVE(转)的更多相关文章

- Stanford机器学习笔记-3.Bayesian statistics and Regularization

3. Bayesian statistics and Regularization Content 3. Bayesian statistics and Regularization. 3.1 Und ...

- 听同事讲 Bayesian statistics: Part 2 - Bayesian inference

听同事讲 Bayesian statistics: Part 2 - Bayesian inference 摘要:每天坐地铁上班是一件很辛苦的事,需要早起不说,如果早上开会又赶上地铁晚点,更是让人火烧 ...

- 听同事讲 Bayesian statistics: Part 1 - Bayesian vs. Frequentist

听同事讲 Bayesian statistics: Part 1 - Bayesian vs. Frequentist 摘要:某一天与同事下班一同做地铁,刚到地铁站,同事遇到一熟人正从地铁站出来. ...

- 贝叶斯统计(Bayesian statistics) vs 频率统计(Frequentist statistics):marginal likelihood(边缘似然)

1. Bayesian statistics 一组独立同分布的数据集 X=(x1,-,xn)(xi∼p(xi|θ)),参数 θ 同时也是被另外分布定义的随机变量 θ∼p(θ|α),此时: p(X|α) ...

- Bayesian Statistics for Genetics | 贝叶斯与遗传学

Common sense reduced to computation - Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace (1749–1827) Inventor of Bayes ...

- Bayesian statistics

文件夹 1Bayesian model selection贝叶斯模型选择 1奥卡姆剃刀Occams razor原理 2Computing the marginal likelihood evidenc ...

- Bayesian machine learning

from: http://www.metacademy.org/roadmaps/rgrosse/bayesian_machine_learning Created by: Roger Grosse( ...

- 朴素贝叶斯分类器(Naive Bayesian Classifier)

本博客是基于对周志华教授所著的<机器学习>的"第7章 贝叶斯分类器"部分内容的学习笔记. 朴素贝叶斯分类器,顾名思义,是一种分类算法,且借助了贝叶斯定理.另外,它是一种 ...

- Machine Learning and Data Mining(机器学习与数据挖掘)

Problems[show] Classification Clustering Regression Anomaly detection Association rules Reinforcemen ...

随机推荐

- android studio 2.3 下载地址

android studio下载: Windows+SDK:(1.8GB)| Windows(428 MB) | Linux idea win.exe win.zip 序号 名称 中文 ...

- 时间同步方法及几个可用的NTP服务器地址

大家都知道计算机电脑的时间是由一块电池供电保持的,而且准确度比较差经常出现走时不准的时候.通过互联网络上发布的一些公用网络时间服务器NTP server,就可以实现自动.定期的同步本机标准时间. 依靠 ...

- UEditor使用------图片上传与springMVC集成 完整实例

UEditor是一个很强大的在线编辑软件 ,首先讲一下 基本的配置使用 ,如果已经会的同学可以直接跳过此节 ,今天篇文章重点说图片上传; 一 富文本的初始化使用: 1 首先将UEditor从官网下载 ...

- HTML、CSS、JS 样式

把一个数组(一维或二维等)的内容转化为对应的字符串.相当于把print_r($array)显示出来的内容赋值给一个变量.$data= array('hello',',','world','!'); $ ...

- oracle 归档日志满 报错ORA-00257: archiver error. Connect internal only, until freed

归档日志满导致无法用户无法登陆 具体处理办法 --用户登陆 Microsoft Windows [Version 6.1.7601] Copyright (c) Microsoft Corporati ...

- [.NET] 《Effective C#》读书笔记(二)- .NET 资源托管

<Effective C#>读书笔记(二)- .NET 资源托管 简介 续 <Effective C#>读书笔记(一)- C# 语言习惯. .NET 中,GC 会帮助我们管理内 ...

- PHP 手册

http://www.php.net/manual/zh/index.php 感谢中文翻译工作者. PHP 手册¶ by:Mehdi Achour Friedhelm Betz Antony Dovg ...

- macOS 中使用 phpize 动态添加 PHP 扩展的错误解决方法

使用 phpize 动态添加 PHP 扩展是开发中经常需要做的事情,但是在 macOS 中,首次使用该功能必然会碰到一些错误,本文列出了这些错误的解决方法. 问题一: 执行 phpize 报错如下: ...

- matlab笔记(1) 元胞结构cell2mat和num2cell

摘自于:https://zhidao.baidu.com/question/1987862234171281467.html https://www.zybang.com/question/dcb09 ...

- FME中通过HTMLExtractor向HTML要数据

如何不断扩充数据中心的数据规模,提升数据挖掘的价值,这是我们思考的问题,数据一方面来自于内部生产,一部分数据可以来自于互联网,互联网上的数据体量庞大,形态多样,之前blog里很多FMEer已经提出了方 ...