The internals of Python string interning

JUNE 28TH, 2014Tweet

This article describes how Python string interning works in CPython 2.7.7.

A few days ago, I had to explain to a colleague what the built-in function intern does. I gave him the following example:

>>> s1 = 'foo!'

>>> s2 = 'foo!'

>>> s1 is s2

False

>>> s1 = intern('foo!')

>>> s1

'foo!'

>>> s2 = intern('foo!')

>>> s1 is s2

TrueYou got the idea but… how does it work internally?

The PyStringObject structure

Let’s delve into CPython source code and take a look at PyStringObject, the C structure representing Python strings located in the file stringobject.h:

typedef struct {

PyObject_VAR_HEAD

long ob_shash;

int ob_sstate;

char ob_sval[1];

/* Invariants:

* ob_sval contains space for 'ob_size+1' elements.

* ob_sval[ob_size] == 0.

* ob_shash is the hash of the string or -1 if not computed yet.

* ob_sstate != 0 iff the string object is in stringobject.c's

* 'interned' dictionary; in this case the two references

* from 'interned' to this object are *not counted* in ob_refcnt.

*/

} PyStringObject;According to this comment, the variable ob_sstate is different from 0 if and only if the string is interned. This variable is never accessed directly but always through the macro PyString_CHECK_INTERNED defined a few lines below:

#define PyString_CHECK_INTERNED(op) (((PyStringObject *)(op))->ob_sstate)The interned dictionary

Then, let’s open stringobject.c. Line 24 declares a reference to an object where interned strings will be stored:

static PyObject *interned;In fact, this object is a regular Python dictionary and is initialized line 4745:

interned = PyDict_New();Finally, all the magic happens line 4732 in the PyString_InternInPlace function. The implementation is straightforward:

PyString_InternInPlace(PyObject **p)

{

register PyStringObject *s = (PyStringObject *)(*p);

PyObject *t;

if (s == NULL || !PyString_Check(s))

Py_FatalError("PyString_InternInPlace: strings only please!");

/* If it's a string subclass, we don't really know what putting

it in the interned dict might do. */

if (!PyString_CheckExact(s))

return;

if (PyString_CHECK_INTERNED(s))

return;

if (interned == NULL) {

interned = PyDict_New();

if (interned == NULL) {

PyErr_Clear(); /* Don't leave an exception */

return;

}

}

t = PyDict_GetItem(interned, (PyObject *)s);

if (t) {

Py_INCREF(t);

Py_DECREF(*p);

*p = t;

return;

}

if (PyDict_SetItem(interned, (PyObject *)s, (PyObject *)s) < 0) {

PyErr_Clear();

return;

}

/* The two references in interned are not counted by refcnt.

The string deallocator will take care of this */

Py_REFCNT(s) -= 2;

PyString_CHECK_INTERNED(s) = SSTATE_INTERNED_MORTAL;

}As you can see, keys in the interned dictionary are pointers to string objects and values are the same pointers. Furthermore, string subclasses cannot be interned. Let me set aside error checking and reference counting and rewrite this function in pseudo Python code:

interned = None

def intern(string):

if string is None or not type(string) is str:

raise TypeError

if string.is_interned:

return string

if interned is None:

global interned

interned = {}

t = interned.get(string)

if t is not None:

return t

interned[string] = string

string.is_interned = True

return stringSimple, isn’t it?

What are the benefits of interning strings?

Object sharing

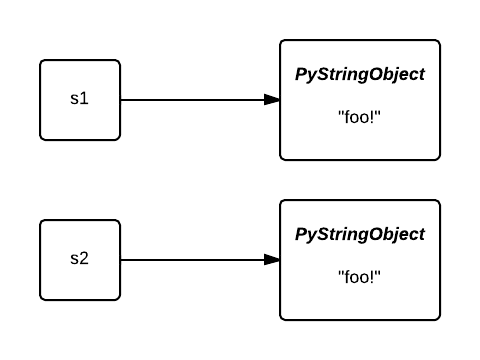

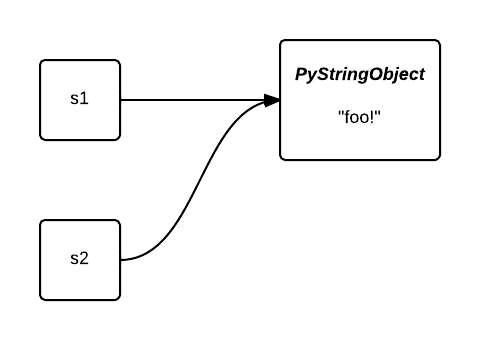

Why would you intern strings? Firstly, “sharing” string objects reduces the amount of memory used. Let’s go back to our first example, initially, the variables s1 and s2 reference two different objects:

After being interned, they both point to the same object. The memory occupied by the second object is saved:

When dealing with large lists with low entropy, interning makes sense. For instance, when tokenizing a corpus, we could benefit from the very heavy-tailed distribution of word frequencies in human languages to intern strings to our advantage. In the following example, we will load the play Hamlet by Shakespeare with NLTK and we will use Heapy to inspect the object heap before and after interning:

import guppy

import nltk

hp = guppy.hpy()

hp.setrelheap()

hamlet = nltk.corpus.shakespeare.words('hamlet.xml')

print hp.heap()

hamlet = [intern(wrd) for wrd in nltk.corpus.shakespeare.words('hamlet.xml')]

print hp.heap()$ python intern.py

Partition of a set of 31187 objects. Total size = 1725752 bytes.

Index Count % Size % Cumulative % Kind (class / dict of class)

0 31166 100 1394864 81 1394864 81 str

...

Partition of a set of 4555 objects. Total size = 547840 bytes.

Index Count % Size % Cumulative % Kind (class / dict of class)

0 4 0 328224 60 328224 60 list

1 4529 99 215776 39 544000 99 str

...As you can see, we drastically reduced the number of allocated string objects from 31 166 to 4 529 and divided by 6.5 the memory occupied by the strings!

Pointer comparison

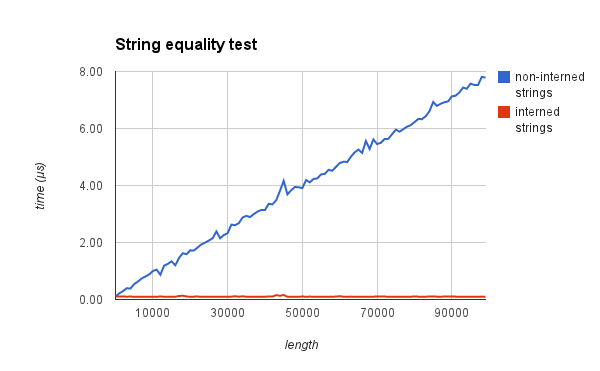

Secondly, strings can be compared by a O(1) pointer comparison instead of a O(n) byte-per-byte comparison.

To prove so, I have measured the time required to verify the equality of two strings as a function of their length when they are interned and when they are not. The following should convince you:

Native interning

Under certain conditions, strings are natively interned. Recall the first example, if I had written foo instead of foo!, the stringss1 and s2 would have been interned “automatically”:

>>> s1 = 'foo'

>>> s2 = 'foo'

>>> s1 is s2

TrueInterned or not interned?

Before writing this blog post, I always thought that, under the hood, strings were natively interned according to a rule taking into account their length and the characters composing them. I was not far away from the truth but, unfortunately, when playing with pairs of strings built in very different ways, I could never infer what this rule exactly was. Can you?

>>> 'foo' is 'foo'

True

>>> 'foo!' is 'foo!'

False

>>> 'foo' + 'bar' is 'foobar'

True

>>> ''.join(['f']) is ''.join(['f'])

True

>>> ''.join(['f', 'o', 'o']) is ''.join(['f', 'o', 'o'])

False

>>> 'a' * 20 is 'aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa'

True

>>> 'a' * 21 is 'aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa'

False

>>> 'foooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo' is 'foooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo'

TrueAfter looking at these examples, you have to admit that it is hard to tell on which basis a string is natively interned or not. So let’s read some more CPython code and figure it out!

Fact 1: all length 0 and length 1 strings are interned

Still in stringobject.c, this time we will take a look at these interesting lines placed in both of the following functionsPyString_FromStringAndSize and PyString_FromString:

/* share short strings */

if (size == 0) {

PyObject *t = (PyObject *)op;

PyString_InternInPlace(&t);

op = (PyStringObject *)t;

nullstring = op;

Py_INCREF(op);

} else if (size == 1 && str != NULL) {

PyObject *t = (PyObject *)op;

PyString_InternInPlace(&t);This leaves no ambiguity: all strings of length 0 and 1 are interned.

Fact 2: strings are interned at compile time

The Python code you write is not directly interpreted and goes through a classic compilation chain which generates an intermediate language called bytecode. Python bytecode is a set of instructions executed by a virtual machine: the Python interpreter. The list of these instructions can be found here and you can find out what instructions are run by a particular function or module, by using the dis module:

>>> import dis

>>> def foo():

... print 'foo!'

...

>>> dis.dis(foo)

2 0 LOAD_CONST 1 ('foo!')

3 PRINT_ITEM

4 PRINT_NEWLINE

5 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

8 RETURN_VALUEAs you know, in Python everything is an object and Code objects are Python objects which represent pieces of bytecode. A Code object carries along with all the information needed to execute: constants, variable names, and so on. It turns out that when building a Code object in CPython, some more strings are interned:

PyCodeObject *

PyCode_New(int argcount, int nlocals, int stacksize, int flags,

PyObject *code, PyObject *consts, PyObject *names,

PyObject *varnames, PyObject *freevars, PyObject *cellvars,

PyObject *filename, PyObject *name, int firstlineno,

PyObject *lnotab)

...

/* Intern selected string constants */

for (i = PyTuple_Size(consts); --i >= 0; ) {

PyObject *v = PyTuple_GetItem(consts, i);

if (!PyString_Check(v))

continue;

if (!all_name_chars((unsigned char *)PyString_AS_STRING(v)))

continue;

PyString_InternInPlace(&PyTuple_GET_ITEM(consts, i));

}In codeobject.c, the tuple consts contains the literals defined at compile time: booleans, floating-point numbers, integers, and strings declared in your program. The strings stored in this tuple and not filtered out by the all_name_chars function are interned.

In the example below, s1 is declared at compile time. Oppositely, s2 is produced at runtime:

s1 = 'foo'

s2 = ''.join(['f', 'o', 'o'])As a consequence, s1 will be interned whereas s2 will not.

The function all_name_chars rules out strings that are not composed of ascii letters, digits or underscores, i.e. strings looking like identifiers:

#define NAME_CHARS \

"0123456789ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ_abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz"

/* all_name_chars(s): true iff all chars in s are valid NAME_CHARS */

static int

all_name_chars(unsigned char *s)

{

static char ok_name_char[256];

static unsigned char *name_chars = (unsigned char *)NAME_CHARS;

if (ok_name_char[*name_chars] == 0) {

unsigned char *p;

for (p = name_chars; *p; p++)

ok_name_char[*p] = 1;

}

while (*s) {

if (ok_name_char[*s++] == 0)

return 0;

}

return 1;

}With all these explanations in mind, we now understand why 'foo!' is 'foo!' evaluates to False whereas'foo' is 'foo' evaluates to True. Victory? Not quite yet.

Bytecode optimization produces more string constants

It might sound very counterintuitive, but in the example below, the outcome of the string concatenation is not performed at runtime but at compile time:

>>> 'foo' + 'bar' is 'foobar'

TrueThis is why the result of 'foo' + 'bar' is also interned and the expression evaluates to True.

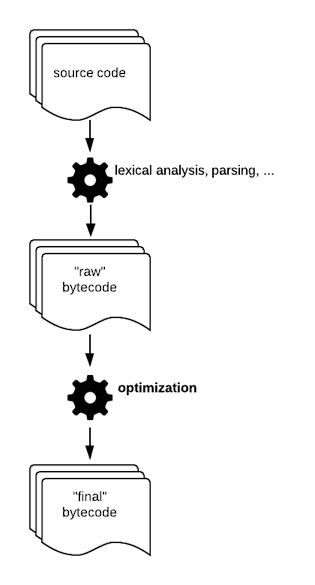

How? The penultimate source code compilation step produces a first version of bytecode. This “raw” bytecode finally goes into a last compilation step called “peephole optimization”.

The goal of this step is to produce more efficient bytecode by replacing some instructions by faster ones.

Constant folding

One of the techniques applied during peephole optimization is called constant folding and consists in simplifying constant expressions in advance. Imagine you are a compiler and you come across this line:

SECONDS = 24 * 60 * 60What can you do to simplify this expression and save some clock cycles at runtime? You are going to substitute this expression by the computed value 86400. This is exactly what happens to the 'foo' + 'bar' expression. Let’s define the foobar function and disassemble the corresponding bytecode:

>>> import dis

>>> def foobar():

... return 'foo' + 'bar'

>>> dis.dis(foobar)

2 0 LOAD_CONST 3 ('foobar')

3 RETURN_VALUESee? No sign of the addition and the two initial constants 'foo' and 'bar'. If CPython bytecode was not optimized, the output would have been the following:

>>> dis.dis(foobar)

2 0 LOAD_CONST 1 ('foo')

3 LOAD_CONST 2 ('bar')

6 BINARY_ADD

7 RETURN_VALUEWe discovered why the following expression evaluates to True:

>>> 'a' * 20 is 'aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa'Avoiding large .pyc files

So why does 'a' * 21 is 'aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa' not evaluate to True? Do you remember the .pyc files you encounter in all your packages? Well, Python bytecode is stored in these files. What would happen if someone wrote something like this['foo!'] * 10**9? The resulting .pyc file would be huge! In order to avoid this phenomena, sequences generated through peephole optimization are discarded if their length is superior to 20.

I know interning

Now, you know all about Python string interning!

I’m amazed at how deep I dug in CPython in order to understand something as anecdotic as string interning. I’m also surprised by the simplicity of the CPython API. Even though, I’m a poor C developer, the code is very readable, very well documented, and I feel like even I could contribute to it.

Immutability required

Oh… one last thing, I forgot to mention one VERY important thing. Interning works because Python strings are immutable. Interning mutable objects would not make sense at all and would cause disastrous side effects.

But wait… We know some other immutable objects. Integers for instance. Well… guess what?

>>> x, y = 256, 256

>>> x is y

True

>>> x, y = int('256'), int('256')

>>> x is y

True

>>> 257 is 257

True

>>> x, y = int('257'), int('257')

>>> x is y

False;)

Going deeper

- Exploring Python Code Objects, Dan Crosta;

- Python string objects implementation, Laurent Luce.

The internals of Python string interning的更多相关文章

- Python string interning原理

原文链接:The internals of Python string interning 由于本人能力有限,如有翻译出错的,望指明. 这篇文章是讲Python string interning是如何 ...

- 什么是string interning(字符串驻留)以及python中字符串的intern机制

Incomputer science, string interning is a method of storing only onecopy of each distinct string val ...

- python string module

String模块中的常量 >>> import string >>> string.digits ' >>> string.letters 'ab ...

- python string

string比较连接 >>> s1="python string" >>> len(s) 13 >>> s2=" p ...

- Python string objects implementation

http://www.laurentluce.com/posts/python-string-objects-implementation/ Python string objects impleme ...

- Python string replace 方法

Python string replace 方法 方法1: >>> a='...fuck...the....world............' >>> b=a ...

- python string与list互转

因为python的read和write方法的操作对象都是string.而操作二进制的时候会把string转换成list进行解析,解析后重新写入文件的时候,还得转换成string. >>&g ...

- python string 文本常量和模版

最近在看python标准库这本书,第一感觉非常厚,第二感觉,里面有很多原来不知道的东西,现在记下来跟大家分享一下. string类是python中最常用的文本处理工具,在python的 ...

- Python String 方法详解

官网文档地址:https://docs.python.org/3/library/stdtypes.html#string-methods 官网 公号:软测小生ruancexiaosheng 文档里的 ...

随机推荐

- SQL知识累积

详细介绍select的文章,展示原始数据.SQL.查询结果,以及在不同数据库下SQL应该如何写. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Select_(SQL) 目录如下: Co ...

- 双nginx(主备、主主)反向代理tomcat实现web端负载均衡

经过以前做完的产品,受前公司几位前辈技术大拿指点,来自己动手实现并总结一下web端的负载解决方法,高手请略过,个人认知有限,请各位指正错误. 下面是结构图: 我的系统环境是Fedora22(适用rea ...

- andriod的简单用法2

1.在Activity中使用menu //创建菜单项 public boolean onCreateOptionsMenu(Menu menu) { // Inflate the menu; this ...

- [Hive-Tutorial] What Is Hive

What Is Hive Hive is a data warehousing infrastructure based on Hadoop. Hadoop provides massive scal ...

- 《Genesis-3D开源游戏引擎--横版格斗游戏制作教程:简介及目录》(附上完整工程文件)

介绍:讲述如何使用Genesis-3D来制作一个横版格斗游戏,涉及如何制作连招系统,如何使用包围盒实现碰撞检测,软键盘的制作,场景切换,技能读表,简单怪物AI等等,并为您提供这个框架的全套资源,源码以 ...

- 《Genesis-3D开源游戏引擎完整实例教程-2D射击游戏篇01:播放序列动画》

1.播放序列动画 系列动画播放概述 2D游戏中的动画系统,不同于3D游戏.3D游戏中,角色美术资源不仅包含角色模型的,还包括角色的贴图和动作等,模型本身自带角色的动作动画效果.2D游戏中,角色美术资源 ...

- Codevs No.1287 矩阵乘法

2016-06-01 16:53:23 题目链接: 矩阵乘法 (Codevs No.1287) 题目大意: 给你两个可乘矩阵a,b,求a*b 解法: 定义....... //矩阵乘法 (Codevs ...

- pomelo windows 环境

1.先安装 Python; 通过Python 官网 http://www.python.org/getit/ 下载并安装最新版本. 然后将Python 的安装目录(如: C:\Program File ...

- 第二百四十一天 how can I 坚持

今天去了趟小米之家,红米note3感觉还好吧.小米,希望不会令人失望啊,很看好的,应该不算是米粉吧. 腾讯课堂. hadoop. 摄影. 没有真正的兴趣啊,一心只想着玩,什么事真正的兴趣,就是无时无刻 ...

- dns解析对SEO产生的影响

DNS 是域名系统 (Domain Name System) 的缩写,它是由解析器和域名服务器组成的.域名服务器是指保存有该网络中所有主机的域名和对应的IP地址,并具有将域名转换为IP地址功能的服务器 ...