Acquire and Release Fences

转载自: http://preshing.com/20130922/acquire-and-release-fences/

Acquire and release fences, in my opinion, are rather misunderstood on the web right now. That’s too bad, because the C++11 Standards Committee did a great job specifying the meaning of these memory fences. They enable robust algorithms which scale well across multiple cores, and map nicely onto today’s most common CPU architectures.

First things first: Acquire and release fences are considered low-level lock-free operations. If you stick with higher-level, sequentially consistent atomic types, such as volatile variables in Java 5+, or default atomics in C++11, you don’t need acquire and release fences. The tradeoff is that sequentially consistent types are slightly less scalable or performant for some algorithms.

On the other hand, if you’ve developed for multicore devices in the days before C++11, you might feel an affinity for acquire and release fences. Perhaps, like me, you remember struggling with the placement of some lwsync intrinsics while synchronizing threads on Xbox 360. What’s cool is that once you understand acquire and release fences, you actually see what we were trying to accomplish using those platform-specific fences all along.

Acquire and release fences, as you might imagine, are standalone memory fences, which means that they aren’t coupled with any particular memory operation. So, how do they work?

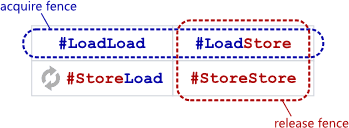

An acquire fence prevents the memory reordering of any read which precedes it in program order with any read or write which follows it in program order.

A release fence prevents the memory reordering of any read or write which precedes it in program order with any write which follows it in program order.

In other words, in terms of the barrier types explained here, an acquire fence serves as both a #LoadLoad + #LoadStore barrier, while a release fence functions as both a #LoadStore + #StoreStore barrier. That’s all they purport to do.

When programming in C++11, you can invoke them using the following functions:

#include <atomic>

std::atomic_thread_fence(std::memory_order_acquire);

std::atomic_thread_fence(std::memory_order_release);

In C11, they take this form:

#include <stdatomic.h>

atomic_thread_fence(memory_order_acquire);

atomic_thread_fence(memory_order_release);

And using Mintomic, a small, portable lock-free API:

#include <mintomic/mintomic.h>

mint_thread_fence_acquire();

mint_thread_fence_release();

On the SPARC-V9 architecture, an acquire fence can be implemented using the membar #LoadLoad | #LoadStore instruction, and an a release fence can be implemented as membar #LoadStore | #StoreStore. On other CPU architectures, the people who implement the above libaries must translate these operations into the next best thing – some CPU instruction which provides at least the required barrier types, and possibly more. On PowerPC, the next best thing is lwsync. On ARMv7, the next best thing is dmb. On Itanium, the next best thing is mf. And on x86/64, no CPU instruction is needed at all. As you might expect, acquire and release fences restrict reordering of neighboring operations at compile time as well.

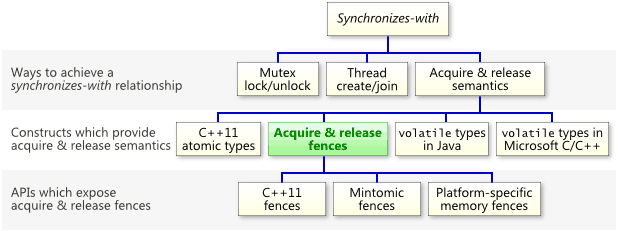

They Can Establish Synchronizes-With Relationships

The most important thing to know about acquire and release fences is that they can establish a synchronizes-with relationship, which means that they prohibit memory reordering in a way that allows you to pass information reliably between threads. Keep in mind that, as the following chart illustrates, acquire and release fences are just one of many constructs which can establish a synchronizes-withrelationship.

As I’ve shown before, a relaxed atomic load immediately followed by an acquire fence will convert that load into a read-acquire. Similarly, a relaxed atomic store immediately preceded by a release fence will convert that store into a write-release. For example, if g_guard has type std::atomic<int>, then this line

g_guard.store(1, std::memory_order_release);

can be safely replaced with the following.

std::atomic_thread_fence(std::memory_order_release);

g_guard.store(1, std::memory_order_relaxed);

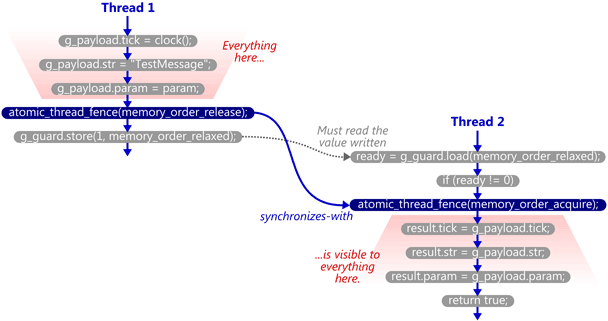

One precision: In the latter form, it is no longer the store which synchronizes-with anything. It is the fence itself. To see what I mean, let’s walk through a detailed example.

A Walkthrough Using Acquire and Release Fences

We’ll take the example from my previous post and modify it to use C++11’s standalone acquire and release fences. Here’s the SendTestMessage function. The atomic write is now relaxed, and a release fence has been placed immediately before it.

void SendTestMessage(void* param)

{

// Copy to shared memory using non-atomic stores.

g_payload.tick = clock();

g_payload.str = "TestMessage";

g_payload.param = param; // Release fence.

std::atomic_thread_fence(std::memory_order_release); // Perform an atomic write to indicate that the message is ready.

g_guard.store(1, std::memory_order_relaxed);

}

Here’s the TryReceiveMessage function. The atomic read has been relaxed, and an acquire fence has been placed slightly after it. In this case, the fence does not occur immediately after the read; we first check whether ready != 0, since that’s the only case where the fence is really needed.

bool TryReceiveMessage(Message& result)

{

// Perform an atomic read to check whether the message is ready.

int ready = g_guard.load(std::memory_order_relaxed); if (ready != 0)

{

// Acquire fence.

std::atomic_thread_fence(std::memory_order_acquire); // Yes. Copy from shared memory using non-atomic loads.

result.tick = g_payload.tick;

result.str = g_msg_str;

result.param = g_payload.param; return true;

} // No.

return false;

}

Now, if TryReceiveMessage happens to see the write which SendTestMessage performed on g_guard, then it will issue the acquire fence, and the synchronizes-with relationship is complete. Again, strictly speaking, it’s the fences which synchronize-with each other.

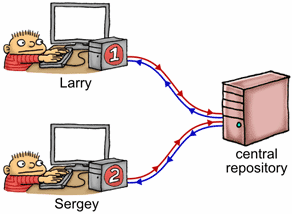

Let’s back up for a moment and consider this example in terms of the source control analogy I made a while back. Imagine shared memory as a central repository, with each thread having its own private copy of that repository. As each thread manipulates its private copy, modifications are constantly “leaking” to and from the central repository at unpredictable times. Acquire and release fences are used to enforce ordering among those leaks.

If we imagine Thread 1 as a programmer named Larry, and Thread 2 as a programmer named Sergey, what happens is the following:

- Larry performs a bunch of non-atomic stores to his private copy of

g_payload. - Larry issues a release fence. That means that all his previous memory operations will be committed to the repository – whenever that happens – before any store he performs next.

- Larry stores

1to his private copy ofg_guard. - At some random moment thereafter, Larry’s private copy of

g_guardleaks to the central repository, entirely on its own. Remember, once this happens, we’re guaranteed that Larry’s changes tog_payloadare in the central repository, too. - At some random moment thereafter, the updated value of

g_guardleaks from the central repository to Sergey’s private copy, entirely on its own. - Sergey checks his private copy of

g_guardand sees1. - Seeing that, Sergey issues an acquire fence. All the contents of Sergey’s private copy become at least as new as his previous load. This completes the synchronizes-with relationship.

- Sergey performs a bunch of non-atomic loads from his private copy of

g_payload. At this point, he is guaranteed to see the values that were written by Larry.

Note that the guard variable must “leak” from Larry’s private workspace over to Sergey’s all by itself. When you think about it, acquire and release fences are just a way to piggyback additional data on top of such leaks.

The C++11 Standard’s Got Our Back

The C++11 standard explicitly states that this example will work on any compliant implementation of the library and language. The promise is made in §29.8.2 of working draft N3337:

A release fence A synchronizes with an acquire fence B if there exist atomic operations X and Y, both operating on some atomic object M, such that A is sequenced before X, X modifies M, Y is sequenced before B, and Y reads the value written by X or a value written by any side effect in the hypothetical release sequence X would head if it were a release operation.

That’s a lot of letters. Let’s break it down. In the above example:

- Release fence A is the release fence issued in

SendTestMessage. - Atomic operation X is the relaxed atomic store performed in

SendTestMessage. - Atomic object M is the guard variable,

g_guard. - Atomic operation Y is the relaxed atomic load performed in

TryReceiveMessage. - Acquire fence B is the acquire fence issued in

TryReceiveMessage.

And finally, if the relaxed atomic load reads the value written by the relaxed atomic store, the C++11 standard says that the fences synchronize-with each other, just as I’ve shown.

I like C++11’s approach to portable memory fences. Other people have attempted to design portable memory fence APIs in the past, but in my opinion, few of them hit the sweet spot for lock-free programming like C++11, as far as standalone fences go. And while acquire and release fences may not translate directly into native CPU instructions, they’re close enough that you can still squeeze out as much performance as is currently possible from the vast majority of multicore devices. That’s why Mintomic, an open source library I released earlier this year, offers acquire and release fences – along with a consume and full memory fence – as its only memory ordering operations. Here’s the example from this post, rewritten using Mintomic.

In an upcoming post, I’ll highlight a couple of misconceptions about acquire & release fences which are currently floating around the web, and discuss some performance concerns. I’ll also talk a little bit more about their relationship with read-acquire and write-release operations, including some consequences of that relationship which tend to trip people up.

Acquire and Release Fences的更多相关文章

- Acquire and Release Semantics

An operation has acquire semantics if other processors will always see its effect before any subsequ ...

- Python用上锁和解锁 lock lock.acquire lock.release 模拟抢火车票

Python用上锁和解锁 lock lock.acquire lock.release 模拟抢火车票 import jsonimport timefrom multiprocessing impor ...

- Lock 深入理解acquire和release原理源码及lock独有特性acquireInterruptibly和tryAcquireNanos

https://blog.csdn.net/sophia__yu/article/details/84313234 Lock是一个接口,通常会用ReentrantLock(可重入锁)来实现这个接口. ...

- C11 memory_order

概念: 摘录自:http://preshing.com/20120913/acquire-and-release-semantics/ Acquire semantics is a property ...

- The JSR-133 Cookbook for Compiler Writers(an unofficial guide to implementing the new JMM)

The JSR-133 Cookbook for Compiler Writers by Doug Lea, with help from members of the JMM mailing lis ...

- Game Engine Architecture 5

[Game Engine Architecture 5] 1.Memory Ordering Semantics These mysterious and vexing problems can on ...

- An Introduction to Lock-Free Programming

Lock-free programming is a challenge, not just because of the complexity of the task itself, but bec ...

- android graphic(15)—fence

为何须要fence fence怎样使用 软件实现的opengl 硬件实现的opengl 上层使用canvas画图 上层使用opengl画图 下层合成 updateTexImage doComposeS ...

- 内存屏障 WriteBarrier 垃圾回收 屏障技术

https://baike.baidu.com/item/内存屏障 内存屏障,也称内存栅栏,内存栅障,屏障指令等, 是一类同步屏障指令,是CPU或编译器在对内存随机访问的操作中的一个同步点,使得此点之 ...

随机推荐

- SSD检测几个小细节

目录 一. 抛砖引玉的Faster-RCNN 1.1 候选框的作用 1.2 下采样问题 二. SSD细节理解 2.1 六个LOSS 2.2 Anchor生成细节 2.3 Encode&& ...

- ssh免密码登录与常见问题

免密码登录 cd ~/.ssh ssh-keygen -t rsa #然后敲回车 mv id_rsa.pub master_rsa.pub cat master_rsa.pub >> au ...

- mysql IFNULL函数和COALESCE函数使用技巧

IFNULL() 函数 IFNULL() 函数用于判断第一个表达式是否为 NULL,如果为 NULL 则返回第二个参数的值,如果不为 NULL 则返回第一个参数的值. IFNULL() 函数 ...

- ZR#957

ZR#957 解法: 首先 $ T $ 必须得要是 $ S $ 的子序列,不然不存在好的下标序列,因此一定无解. 考虑判断一个串 $ T $ 是不是 $ S $ 子序列的贪心做法:每次从没有匹配的位置 ...

- zabbix(x)

问题现象: 客户端设置好自定义监控项,脚本执行或者命令执行都可以正常的输出,但是服务器端通过zabbix-get从客户端获取数据的时候,获取到不正常的值(比如客户端获取到1,服务端获取时显示0或者直接 ...

- 小程序 image跟view标签上下会有间隙

图片文字等inline元素默许是跟父级元素的baseline对齐,而baseline又和父级底边有必定间距 我是使用: 加上这个消除了间隙,如果没有解决,你可以分别用 vertical-align:t ...

- ICEM-圆柱与长方体相切

原视频下载地址:https://yunpan.cn/cqvgLe39ZU4Ke 访问密码 c1c9

- 代码检查p626

1 编译运行p626 图10-3代码,提交编译运行的截图 2 STDOUT_FILENO的值是多少?提交在Ubuntu中查找这个值的命令截图

- MySQL 8.0: From SQL Tables to JSON Documents (and back again)

MySQL 8.0: From SQL Tables to JSON Documents (and back again) | MySQL Server Bloghttps://mysqlserver ...

- el-table的type="selection"的使用

场景:el-table,type="selection"时,重新请求后,设置列表更新前的已勾选项 踩坑:在翻页或者changPageSize之后,table的data会更新,之前勾 ...